“Wow, that’s more than I planned to spend…” If you bid often enough, you’ll hear something like this eventually. Before we go into rescue mode, let’s take the opportunity to really consider why this happens. I believe there are three main reasons that projects come in over budget.

#1. Design professionals bear no responsibility for the relationship between market pricing and their construction documents.

#2. Estimates are “free”.

#3. Clients working with borrowed money learn how much they’re approved to spend after the bid proves market value to their financier. Sometimes, the financier approves less funding than the client planned for.

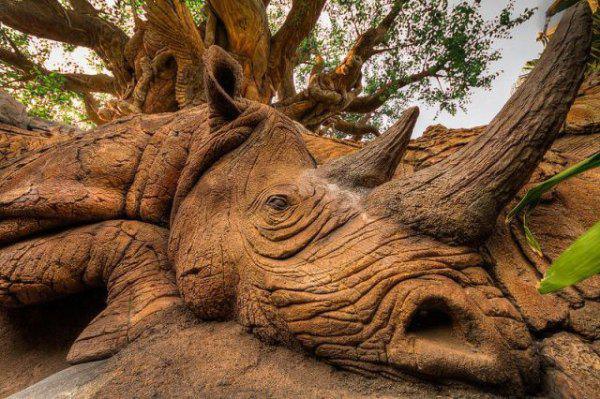

Spotlight on Architects

In some ways, it’s understandable why Design professionals would seek strong separation from design and price. The training, skills, and experience necessary to gain entry to this profession are impressive. Unfortunately their training in management, mediation, contract law, scheduling, and estimating is scant. Nevertheless Architects often provide owners rep services which gives them contractual authority over the General Contractor (GC) for the project.

Negotiating the costs of changes to the plan could hardly be impartial if Architects faced strict liability for the additional costs their client incurred. Most change orders are driven by design shortcomings because it’s REALLY difficult to custom design something perfectly. The best Architects recognize the nature of the business and mediate accordingly. Their mistakes are cheaply fixed.

All of which makes two arguments

The first is that lacking formal training in management, estimation, and contract law, Architects should hardly be the clients first choice for owners rep. Architects have a difficult enough job in designing the project on its own. Of course Architecture firms could hire Construction Managers to fill this shortfall, but that requires admitting fault in the status quo.

The second, is that Architects with experience have ample opportunity to see the market value of their designs. Requests for Proposals (RFP) often demand pricing breakdowns to show how different building components drive the total project cost. Architects are flush with incredible amounts of cost data that they never paid a dime for. This makes it difficult to believe that Architects have genuine basis to be surprised when their project comes in over budget.

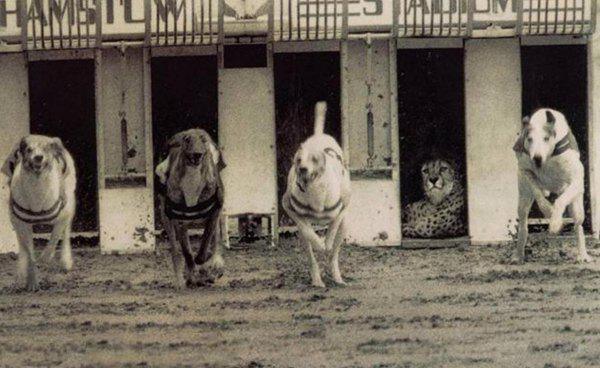

“Ok guys, on the count of three, everybody look surprised. One…Two…”

Conceptual bidding: it’s always your risk

In an effort to prove due-diligence to their clients, many Architecture firms have several rounds of competitive conceptual pricing. Conceptual pricing is a courtesy the market extends to design professionals. Demanding competitive pricing without any promise of contractor selection isn’t reasonable. That’s like holding a charity auction without a prize.

Architects who are conceptually pricing work that’s similar, if not identical to their “bread and butter” type of project aren’t gaining new information. As professionals, Architects need to respect how costly their practices are to the market.

For example: A modest commercial interior build-out may require as few as 20 and as many as 50 individual subcontractors . If the GC invites an average of four bidders per trade, that’s 80 to 100 companies working on the estimate for that project. Some trades will require the assistance of their suppliers or vendors to price portions of their work. That might add another 20-30 firms that are involved across the board. Averaging two hours for each estimators time that comes to 200-260 hours of labor for a single GC’s bid list. If we charitably average what each company’s paying these estimators at $25.00/ hour that means the conceptual estimate cost the local market $5,000.00 to $6,500.00. Most competitive bids have three or more bidders bringing the single estimate cost to $15,000 to $19,500. Design development typically have three rounds of pricing before the final bid bringing the total market cost to $45,000-$58,000

In many cases the market cost is greater than the final build team can hope to profit from the eventual job. Some Architects won’t even give the conceptual bidders an invitation to bid the final project until they’ve worked their way up to the short-list of qualified bidders. The problem here, is that getting onto a short list means someone’s got to come off. Paying your dues has less to do with your performance than anyone wants to admit.

Some Architecture firms request bids for literally hundreds of projects a year with only a handful that ever get built. These Architecture firms should note how the adversarial nature of construction management grows its roots early in the process.

Bids are not free

GC’s who are “feeding the bears” by participating in competitive conceptual bids assume part of the responsibility for their malignant growth in the industry. If a GC wants to make inroads with an Architecture firm by donating their time to conceptual pricing, they need to limit the donation to their own resources. GC’s have extensive backlogs of information on past project costs. There’s no reason for GC’s to burden their subcontractors with needless conceptual efforts. When the plans are so vague, square foot conceptual pricing will suffice. An occasional question to a trusted subcontractor pertaining to the nuance of the scope is certainly acceptable.

The reason GC’s throw this out to competitive bidding is because they aren’t using estimators. An estimator worthy of the title would be able to handle this in-house quickly and inexpensively. The purpose is to provide rough order of magnitude (ROM) budget pricing based on a blend of historical costs, unit pricing of specialty items, and risk factor assessment.

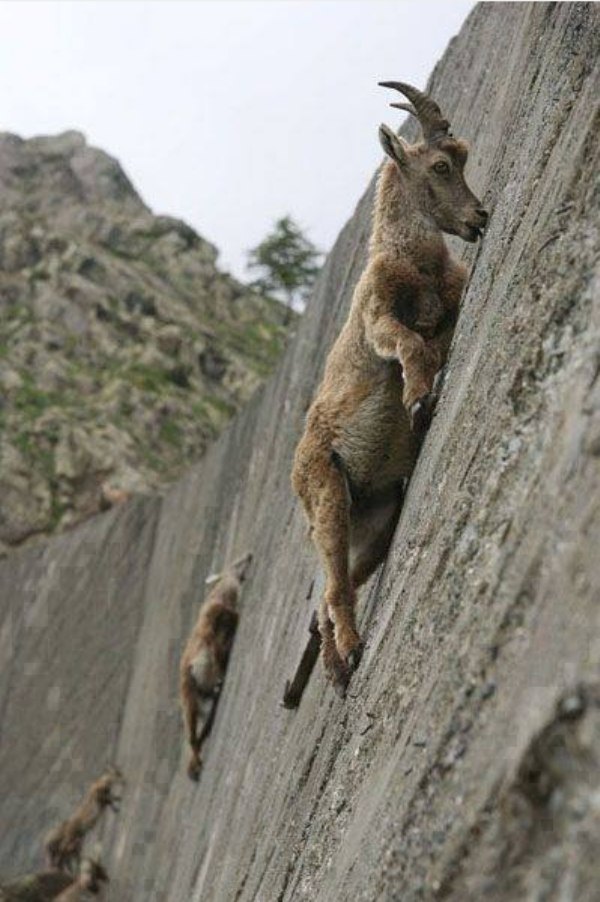

Headed downhill and picking up speed…

Project Managers (PM’s) are often pressed into estimating their own jobs. These conceptual estimates are thrown on their desks as though they’re viable opportunities. Lacking the experience of an estimator, they seek to control their risk by tying all project responsibility to subcontractor proposals. They get these subcontractor proposals the only way they know how: competitive bidding. Demanding subcontractor competition on dead ends is why PM’s end up pounding the phones on bid day claiming “nobody’s looking at this job“.

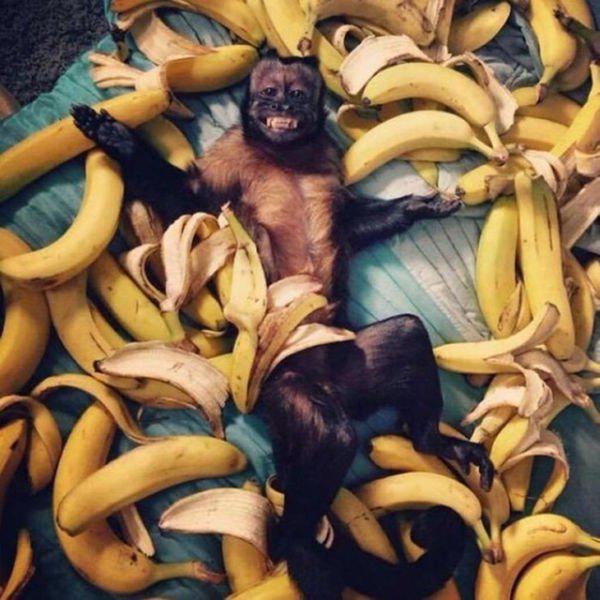

Bob could never figure why he’s got the whole lake to himself…

“But you get to help me for free!”

These PM’s bids are little more than the sum of subcontractor proposals plus fee. This creates an opening for trouble because PM’s are counting on the subs to accurately cover the GC’s risk. The allure of helping the PM’s quickly fades for subs who see the PM becoming a liability. Eventually sub bids become historical square foot pricing, that’s multiplied by a frustration factor. PM’s might be surprised to learn that this frustration factor plays a role in “real” bids as well. Subs may be unwilling to give these PM’s their best efforts because the PM’s refuse to control their own risk. Put another way, PM’s aren’t competitive bidders when they’re not serious about estimating. It’s awfully hard to be serious about estimating when you’re busy managing current jobs.

Pay attention to intention

Conceptual plan sets are a HUGE risk because people will only remember the lowest price you gave them. As illustrated above, the Architect is sitting on a HUGE amount of cost feedback that should steer their course. Nevertheless if your number gives them an excuse, they might swerve the whole job into the ditch chasing it. The design team often treats the conceptual estimate as a “check number” against their clients budget. Low conceptual prices are interpreted to mean they’ve got more money to spend. Design teams collecting a percentage of final contract value have an incentive to maximize the budget.

Above and beyond this, Architects typically allow their consultants to lag substantially in the design. This means that they’ll pipe up about some mandatory (and expensive) engineering concern after the conceptual pricing. PM’s who are used to building to the letter of contract documents (CD’s) quickly learn that conceptual estimating doesn’t play by those rules.

GC’s with overly optimistic conceptual pricing often face their client’s anger later on. Since the Architect proved their due diligence via conceptual pricing, the client assumes the GC’s suddenly got greedy. Neither the Client nor the Architect wants to hear your excuses about how the plan changed, or how you just won their competitive bid!

I really hope nobody told you this would be easy!

The shifting sands of finance

Prospective clients must often pursue financial backing during design development. Financial institutions must carefully guard their shareholders assets by scrutinizing every loan application. Since the final cost of a construction project is not defined until the final bid, it’s understandable that financiers hold off on final decisions until that time. Depending on a variety of factors, the financiers may opt to loan less than the client anticipated. Since the client’s anticipated budget was the basis of the Architects’ design, a natural impasse is formed leaving the client with diminished prospects for getting their project built. Client credit worthiness aside, there are some factors to consider.

In order to get started, the client must present a proposal to their financiers showing how they’re assured recompense from the venture. Part of this is showing how the construction budget is reasonable and in line with market value. In other words, a feasibility study. This stuff extends way beyond the desk of an estimator but at some level, the client needed to prove that spending the construction budget to build the job would be a good idea.

“The Chairmen think your bridge project is too expensive…”

Says who?

Historical data is the perennial treasure chest of answers to all conceptual estimating questions. What establishes historical data? Whatever the last people paid for something similar near you. Cities, Counties, States, Realtors, Developers, and Lawyers all track this information for their dealings on the market. There’s even a subset of construction estimating called “forensic estimating” which investigates anything from a simple construction contract to an entire land development operation.

In practical terms this means that developing in a new area without historical pricing means you’ll have greater risk. It also means that if your neighbor got a great deal, you’re going to have to work with less.

All these various resources are brought to compare with the final budget amount. Financiers may seek to lower their risk by demanding greater surety, higher interest, or lowering the loan amount. Commercial businesses fail all the time. Lenders are very aware of this fact and loan accordingly.

Potential solutions

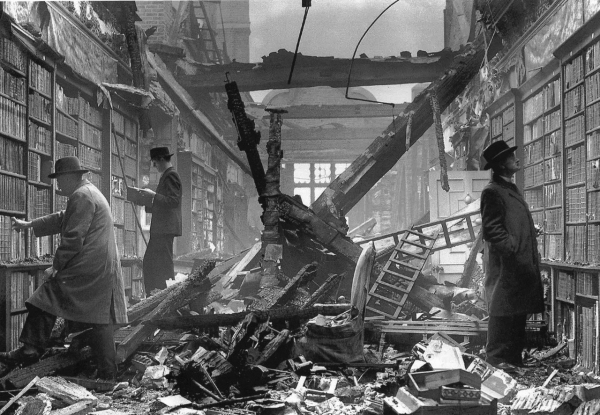

Clearly there’s room for improvement in the traditional design-bid-build process. Budget blowouts are depressingly common, especially during slow markets. Everyone needs these projects to happen with less risk, cost, and time. Thankfully, technology might have provided an answer.

Building Information Modeling (BIM) is a computerized method of integrating the physical properties of building materials into design and management. This is different from Computer Aided Design (CAD) because CAD is mostly a substitute for drafting. BIM is an advancement of CAD that allows Architects to model the building. Some even output to 3-D Printers to create physical scale models.

BIM theoretically allows a design team to output decision-making information. I attended the thesis presentation of a research group who were using BIM to optimize residential home design. The team was able to remove 30% of the structural framing, 25% of the plumbing, among many other savings while retaining or even exceeding the merits of a traditional design. The BIM design cycle didn’t require extensive contractor bidding because the building materials were synchronized to industry recognized standards for pricing. By the time these designs are ready for contractor bidding, the variance in market conditions is very small. Extending beyond the bid, BIM systems offer an impressive degree of building management information. One such system could output scheduled maintenance for the entire building for the next 50 years.

While BIM certainly offers a much-needed connection between design and cost, it’s primarily in use at the highest echelons of the market. Therefore it’s best viewed as a helpful product that’s still on the distant horizon for the rest of us. I’ve been hearing about the imminent usefulness of 3D designs for about 20 years now and aside from “fly through” animations for client presentations, I’ve never seen it on a project that got built. Progress with this stuff is much slower than advertised. I strongly suspect it’s because its disruptive to the status quo. If Architects were autonomously developing a design that met the budget on their first try, the entire paradigm would change.

Pick your team early

Teaming up with a GC early on in the process is a low-tech option that ties design development to costs early on. In excellent examples, the Architect and the GC work together effectively. Others are just boondoggles. GC’s awarded these negotiated agreements run the gamut from top of their class, to bona-fide hacks. Tax-exempt entities tend to award dodgy GC’s.

But he looks so confident!

Perhaps membership in related religious, charitable, and social groups opens the door for them. It’s always a shame whenever it happens. Clients need to award based on proven past performance. For example, don’t hire anyone who’s paid damages for delays! The worst companies are always late and full of excuses. Lots of GC’s have never been late on a project.

You get more of what you encourage

Like most things in life, the greater the incentive, the harder people will pursue it. Clients with limited funds can not afford to work with unprofessional firms. It’s difficult to impress the need to do less with less in order to make the work profitable for good firms. Shoe-string budgets should buy good shoe-strings not building additions. Clients focused exclusively on stretching their own budget rarely consider the economics of an equitable exchange.

Ritchie doesn’t like to share

The work must be profitable for the design team and the build team. Work started with the appearance of unprofitable contract award, often leads to pilfering. By starting with fair-dealing, the client can get better value.

Compartmentalize the conceptual

I believe it’s obvious that Architects should be responsible for designing to the budget. That involves comparing this client to other similar clients and adjusting their design-to budget to what has been historically approved by financiers.

Building systems can be categorized and compartmentalized for conceptual purposes. For example, the budget may include $24,000 for all acoustical ceiling systems. The design may have 16,000 square feet of such systems, are you holding to a reasonable square foot price? Any necessary market-pricing is therefore reduced to specific areas of concern. It’s time for Architects to be aware of the dollar impact of their decisions.

Tracking these decisions through the design could supplant the competitive conceptual bidding. In order to make all of this “stick” the Architecture firms will need to hire qualified construction estimators. The obvious problem of this solution, is that Architects are currently getting this service for free. Which leads to…

Stop feeding the bears

Free bids shouldn’t apply to consulting. Bids are free because the client/Architect didn’t charge anyone for admittance onto their bid list. They represent portions of contractual development. Request for proposal, bid, contract award to best bidder, and so on. Conceptual bidding is not at all the same. Professional courtesy is being abused.

Conceptual pricing utterly dominates the market in slow times. Architects routinely blow their clients budget after months of wasteful conceptual bidding. Some project re-emerge every fiscal quarter only to blow their budget again!

Architects who earn a reputation for wasting bidders time should expect the market to lose interest in them. GC’s who lose all the time aren’t attracting the market leading subs who could change their odds of victory. Architects need to lose business for being unprofessional.

Eventually people stopped coming to Troy’s parties

Blowing their client’s budget isn’t “part of the process”. It’s the direct result of ignoring the business interests of all concerned in the deal.

At a bare minimum, Architects looking for conceptual pricing should expect to pay for the help. Open invite competitive conceptual bidding would immediately stop if every bidder involved got just $50.00 for their efforts. GC’s offering to help could provide an upper limit to their estimates cost, thereby limiting the number of subs involved. Small projects would stop being conceptually bid altogether because Architects might suddenly recall all those old bids… And of course, the Architecture firms would regard hiring their own estimator in a more positive light. Progress would be made.

Construction Manager

Client’s may elect to hire a Construction Manager (CM) to be their owners representative. On the surface this has many advantages because a CM is eminently capable of assessing the strengths and weaknesses of the contractors and the design team. The results can be impressive. I’ve been on both sides of the fence with CM’s and I can say that a truly professional CM can smooth out the kinks better than other contractual relationships. There is however, one snag. In most cases hiring a CM is viewed as “extra cost” because the Architect typically handles these duties. CM’s may try to prove their worth by generating a stack of vetoed change orders, or forcing the design team to accept Value Engineering solutions. These dollar impacts go towards defining the value of the CM’s oversight.

The buffalo grass solution saved on mowing but created other…problems

There’s a difference between good leadership and trophy hunting. Driving the project into an adversarial morass over changes to the scope is a common result of an overzealous CM. Qualified CM’s cost money. Expecting CM’s to fund their services out of project savings isn’t effective. Prioritizing cost and design gouging over project delivery is the problem CM’s are there to solve.

A few words for the clients

The first time client faces a great many challenges in getting their project built. Everyone who knows what to do is a competitor, and everyone else is selling something. Picking the right Architect can substantially influence your odds of success. Clients can’t ask GCs because they are afraid of angering Architects they might have to work with again. First time clients may have different priorities. Some of the worst Architects I’ve ever worked with have testimonials on their websites talking about how wonderful they were about managing conceptual changes. Nobody wrote about how they were on hitting the budget, or the project deadline. My bet is the answer to those questions would have clients running away.

Run Ritchie! Run!

Hiring a CM, especially one who’s retired from General Contracting is a great way to capitalize on experience without the diplomatic hesitation. These folks may have decades of experience in a market leading them to know the top players in all disciplines. Clients might consider hiring them as a consultant to get the “lay of the land” in terms of recommended design teams and contractual relationships.

Asking tradesman and material vendors is a spotty resource at best. Lots of companies love weak design teams because of the rich change order potential. Some vendors are better represented and protected by design teams specifying their expensive products. Still other companies will unfairly judge an Architect based on the engineering consultant they hired. Plus it’s important to understand that few subcontractors will ever actually work directly with an Architect. Everything is through the GC who may filter out, or add in whatever made their experience memorable.

Those aren’t soap bubbles…

Clients should insist that their contract terms with the Architect include proviso’s for blown budgets. At a minimum, the timely revisions necessary to get the budget in line for contract award should be included. Hopeless and hapless requests for Value Engineering post bid are a terrible solution to a problem started at the beginning. Design teams need to see an incentive for saving money and building to a reduced budget. Heading into the final bid, the design team could present their estimated budget and the savings they built-in to it in anticipation of funding shortfalls, or design oversights. Projects are built with contingency, they should be designed with contingency as well. Clients should understand that rushing to bid an incomplete design is false economy. Risk is expensive.

Clients might consider disclosing financial information to the bidding team with greater accuracy. Lots of project RFP’s go out without an estimated budget provided. Clients are stingy with financial feedback, much to their detriment. Public bid-readings complete with the names of all apparent low subs at bid time will go a long way towards curbing bid-shopping. Publishing the CSI breakdown and list of subs for all responsive bids within 24 hours proves a level of honesty that deters cheaters and improves the market. Committing to working with the low bidder even if the budget is blown is the fair and ethical action. If the budget gap is insurmountable, the bid should be considered a loss for all. A serious reassessment of the design team, the financier, and the local market is in order. Sort out what’s wrong and return with real solutions. At a minimum, a client sharing this information is sowing the seeds of honest dealing. Rewarding the best and informing the rest leads to a more prosperous and robust market for all.

For more articles like this click here

© Anton Takken 2015 all rights reserved