Looking back over the years I think the most important things I’ve learned about estimating come down to reading the situation and responding accordingly.

If estimating is only about containing risk, the pursuit of a risk free job will all but guarantee that you’ll never be competitive. There must be some balancing point between acceptable risk and staying competitive. Really often this balancing point rests on the design teams alignment with owner requirements.

Whoa! That’s expensive!

There are a host of reasons why a design team would choose an especially expensive product or assembly. Some are more valid than others. The American Institute of Architects position is quite clear; Architects should never be responsible for cost outcomes. In reality, if the budget is blown by an inefficient design something needs to change to make the project happen. In my experience, weak design teams blow their clients budgets regularly.

Breakout till you break down.

Here’s where we get to some pitfalls. Lots of General Contractors will attempt to demand breakout pricing of the project from their subs. On the surface this seems like a decent first step since you might find some big numbers that could be trimmed.

In reality it’s much harder to just lop off a section of the project free and clear. Engineering concerns, aesthetic issues, and final usability all come into play.

I suppose some GC’s are hoping to get enough information from their subcontract bids to drive down the subs overhead and profit. This is a game they won’t win because it’s cheating. Market value was established by competitive bidding. As hard as it may be to accept, it doesn’t matter if the low bidders markup is obscenely high because they proved they are the best value.

Lots of times GC’s will push out a laundry list of “what if’s”. Often these are generated by a frantic client during a meeting with the GC, and Architect.

Here’s the thing: as an estimator it’s on you to know what will and won’t make the budget overrun disappear. Putting your subs through endless exercises that you know can’t/won’t achieve that end is a waste of your time.

Poorly crafted or worded “what if’s” all but guarantee that you’ll be arguing about scope inclusions for ages. Be especially careful about What-if’s that hinge upon engineering input. Architects rarely seek their consultants input at the negotiating stage. It’s incredibly common for weak design teams to put a GC through several rounds of pricing before issuing a final “construction set” that includes a new and costly engineering necessity.

Most subcontractors view the “what if” stage as a risk generator. I’ve seen some who seek to exploit the confusion hoping to gain profit, and I’ve seen others who fall victim to their own honesty when a GC uses the information to strip the value out of the job. It’s very important to maintain perspective here. These subs got you into the winners circle. Exploiting subcontractors for information to “close the deal” is not your birthright. Threats, cajoling, or short deadlines are the tools of the foolish and shortsighted.

Sure Mikey, I’ll get RIGHT on that for you…

If your client really needed to move forward with their project, they’d have taken steps to ensure their design team would perform within budget before the bid.

None of which is to say that it’s not reasonable to pursue a job that’s over budget. The main aspect that makes an approach successful is sound strategy. Simply put, if you don’t know how far off they were, you can’t really help them. The AIA advises its members to conduct extensive interviews with potential clients. These interviews go deep into the client’s budget, the approval process, advocates and opponents relevant to funding, and so on. The design team knows far more than they will let on about the job budget. Traditionally the Architect serves as owners rep for the project duration. They’re cagey about the budget to protect the client’s interests. Generally the project budget will have a contingency fund which the Architect must be cautious to protect since it pays for unexpected issues, design problems, and so on.

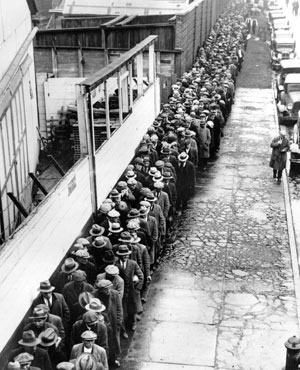

Find out the budget over-run and REALLY consider that information. We hear a lot of inspired speeches about the importance of optimism but the reason that GC’s even exist is because a client can’t reasonably expect to hand the plans to subcontractors and have the job built on time and within budget.

Building on the assumption that the budget over-run is achievable it’s time to review your options to generate an effective strategy. Looking at the subcontractor bids, are there any that seem higher than a similar project would call for? Build a rough tally of what these differences might be. Work your way through all the bids and figure out what you could reasonably carve out. Bear in mind that decorative items have wildly varying prices. If one trade in particular strikes you as profoundly expensive, then it’s worth having a conversation with that bidder to determine what’s driving their costs. Asking for rough numbers in a conversational manner keeps things from becoming a brainstorming session. If you find that a major cost center is due to a sole specification you should try to get a handle on what a competing product would save you.

I’ve seen some bids drop by over half via simple product substitution.

Seven lamp octolights with custom ink-stained shades don’t come cheap…

Corruption is expensive and complex. Don’t think you can simply cut it out of your project without repercussion. It bears mentioning that incompetence is more common than malice. A great deal of specification data is generated “for free” by vendors courting the design team. These vendors put a lot of effort into “helping” the design team with the “nuts and bolts” of their project. This much akin to lobbyists writing sections of proposed laws for congress.

They get their compensation via sole-specification and the outcome is often expensive. The design team will protect their vendors on whatever grounds they see fit. They’ve invested considerable time addressing each issue of the project and it’s their role to ensure that the integrity of their design is built. The client is paying for a level of quality that the design team ensures is provided.

Many GC’s are afraid to anger the design team with Value Engineering suggestions which leads to the aforementioned practice of bombarding them with a myriad of “What if” scenarios.

Really often the client has no idea of the extent to which a sole specification is driving the budget. I bid a project where the square foot cost of a single trade was greater than the total built square foot cost of a similar adjacent property!

That level of brazen price gouging is only possible when the vendors are VERY sure that the design team will protect them. The game is rigged and you’re in a pickle so what do you do? That’s a tough question. Obviously you’re the low bidder if you’re in front of the owner so you’ve gone quite a ways to proving you’re market value.

Personally I think it’s time for a sidebar conversation with the client. Their design team has brought a certain level of corruption into the project but they still work for the client. Clients rarely demand that their design team prove their due diligence with respect to the project budget. The AIA specifically advises its members to avoid any contractual responsibility for the final project budget which might explain why it doesn’t happen much. Nevertheless, the client has options. They can direct the design team to accept performance based alternate equals via a published addendum. They can also opt to establish a “National Account”. More on that in a moment. I purposely stipulated a “published addendum”. Supply chain relationships are very insular. A distributor’s relationship with a rep is far more significant than a single job. Some reps won’t step up and offer an alternate if the design team is notorious for corruption/refusing alternates. By issuing a drawings set with clearly requested value engineering, the design team is forced to acknowledge that “the game is up”. It also clarifies what the design team considers relevant performance data. Again, sometimes a specific product is unique and has a valid reason for inclusion in the design. One pitfall to this is the fairly standard practice of requiring all alternate materials to be approved prior to the bid. Depending on the amount of time from bid letting to deadline, this can often mean it’s not feasible to get alternate materials approved before the deadline. Don’t forget that the design team is invested in their project so they’re not looking to have the design changed by subcontractor suggestions. If they were interested in lowest common denominator materials, they’d list performance specifications to start with.

National Accounts are commonplace among chain restaurants, banks, and some stores. The client establishes an account with a material distributor who publishes the unit costs of each item. This gives the client a chance to scrutinize the design team’s choices and it ensures that all trade bidders get the same material price. National Accounts solve a lot of problems inherit to local corruption however they introduce their own idiosyncrasies as well. First off National Accounts rarely offer best value on everything they include. If the client elects to have subcontractors purchase the materials through national accounts, it adds a layer of complexity since the National Accounts reps must rely on the Subcontractors Quantity Take off (QTO) measurements. I’ve won and lost jobs because of differences in QTO. Getting a National Account rep to give you a unique quote because you’re the only one who noticed that the scale was mis-labeled is all but impossible. I’ve caught something significant in the past and was rewarded by a National Account Rep who notified all my competitors of their mistake. This decreases the incentive for smarter bidders to participate since they can’t capitalize on their expertise.

When the owner furnishes material they take on the risk incurred by having no check on the design team’s measurements. They also take on the risk associated with delivery, billing, and payment for each vendor they contract with. Since material delays would be outside of the build teams control, the client could provide their own undoing. In my experience owners lack the “pull” necessary to get material vendors to correct mistakes in a timely fashion. Obviously the more prominent the client’s account, the more pull they’ll have. Keep in mind that a lowly subcontractor likely purchases millions of dollars of material annually. Their vendors are very committed to overall revenue and that makes a huge difference in their performance.

The client needs to know authoritatively how much they’re being ripped off which will require you to provide historical data on what previous projects have cost. Speak plainly as the design team may be beholden to these vendors who are ripping the client off. The design team may wail and swear that such isn’t the case but that it’s necessity that brought these people to bear. They may claim extra charges to “re-design” elements to achieve your budget which was impacted by dozens of unforeseen issues. Advise your client that they pay the design team for work completed. If the team sublets portions of the design to vendors in exchange for exclusive supplier rights then it seems only fair for you to know beforehand what their final cost will be. This hidden detail is the exposed thread that unravels the whole thing. The industry works on relationships and not all of them are healthy.

Sometimes you can just feel their contempt…

If your client’s facing this situation it’s time for the Architect to call in a solid with their cronies to get the job on budget.

Pretending that this or that valid thing changed to suddenly get the price in line is what causes all the “what if” scenarios. If other similar work is getting built for less, then the design team is making excuses. Many times Architects and their consultants will demand unit pricing for the expensive items. This is a desperate search for ways to pin the blame. The root cause is a vendor overcharging because they know they’ll be protected. The subcontractor can’t risk angering the vendor because they’ll work together again. The Subcontractor’s also in a bind because answering the GC’s unit price questions puts out answers that can and likely will be used against them. Competing vendors may be disinclined to offer other options if they’ve got irons in the fire with the specifier. The more corrupt the design team, the less help you’ll get from the market to fix it. I’ve witnessed projects bidding semi-annually for three years in a row. They celebrate their bid anniversaries by coming in so over-budget that it boggles the mind. The vendor’s responsible can’t/won’t cut their price because they’ve exposed themselves before. Without a team overhaul or a budget boost, the job will never happen. It’s a terrific shame that parasitic situations persists.

The flip side of this is a client who’s so cagey that nothing is ever cheap enough. Developers are notoriously given to speculative bidding. They’ll ask for value engineering ideas from all bidders with immensely detailed breakouts. They’re always one unanswered question away from inking a deal. Weeks and months later, they put out a revised set of drawings that incorporate all of your best ideas. You get the privilege of competing again and again and again. I’ve encountered GC’s who spent so many labor hours bidding the job that they couldn’t re-coup the cost once it finally went to contract.

It’s really important to realize that these people aren’t stupid. They may know that your bids are spot on and that your pre-construction efforts will save them huge amounts. They may also know that once you’ve pounded out all the risk for them, they can go ahead and hire a less sophisticated competitor at lower cost. It’s not that they’re evil, they’re just working the system with people who play along.

This brings me to another experience learning point. Certain subsets of any given market will be populated with a distinct class of professionals. Much of the pairing between client, contractor, and design team comes from a shared level of professionalism and ethical standard.

Despite all the rhetoric about how wonderful everyone is you’ll likely see that weak design teams tend to work for clients that create less competition for their work. Undesirable clients are a magnet for weak design teams. Clients that are broke, “run by committee” or run by a politically connected and unqualified person are disinclined to see the value in a higher level design team.

The less vested a client is to the project’s outcome, the more nonsense you can expect. Gaming the bid with a myriad of alternates allows these individuals to max out their budget with less management interference. It’s these projects that routinely blow their base bid budget because the client’s focus is on spending their allotment entirely rather than building efficiently.

The Design team’s vendors know that the base bid is the low hanging fruit so they load on their profit there. Unsurprisingly the budget is blown. At the GC level it’s apparent how sincere the alternates are when you track through the documents to see if they’re carried to all project scope. For example, there may be a page in the Project Manual listing an alternate for a different ceiling layout. If the Architectural sheets have reflected ceiling plans showing both base and alternate conditions, make sure the Mechanical and Electrical sheets do as well. It’s incredibly common for Architects to pepper their sheets with alternate requests that they never comprehensively list elsewhere. Force the design team to fully acknowledge their alternates via Request For Information (RFI’s.) Badgering your subs on bid day to know that some tiny key-note on the architectural page effects their bid isn’t their job, it’s yours made harder by a weak design team.

Strictly speaking if an alternate exists, you have a duty to provide pricing for it or risk having your bid rejected as incomplete. Be very cautious with this because poorly defined work is higher risk. If you are obligated to use a supplied bid form, you can reliably expect there will be no provision for clarifications, exceptions, exclusions, or contingencies in the single line provided for each alternate price. The client requiring a bid form understandably wants “apples to apples” pricing comparison between bidders. It is therefore critically important that every alternate request be fully vetted at the request for proposal stage. File RFI’s as needed, consult with subs, and control the risk. Discovering that you’re “on your own” to price some murky alternate on bid day is a bad place to be. More than one half-hearted alternate request was revoked following a serious inquiry from a GC.

For more articles like this click here

© Anton Takken 2014 all rights reserved